Sam Martine was a beloved drawing and illustration instructor whose unique approach to teaching was insightful, articulate, and completely free of ego.

Sam was born in Brooklyn, the youngest in a large family that would move to Queens when he was seven years old. He joined the Air Force during the Korean War but never saw action. He spent the bulk of his time in the service as a sergeant stationed in France, where he met his future wife, Janine.

When they returned to New York, he enrolled at the School of Visual Arts on the G.I. Bill. He studied under Robert Weaver, Jack Potter, and Burne Hogarth — who co-founded the school with Silas Rhodes. It was the young instructor Phil Hayes who championed Sam’s gifts most. Sam joined Phil at Lester Rossin Associates — the elite creative agency of the day — and Silas hired Sam to teach at SVA in 1966, all on Phil’s recommendation.

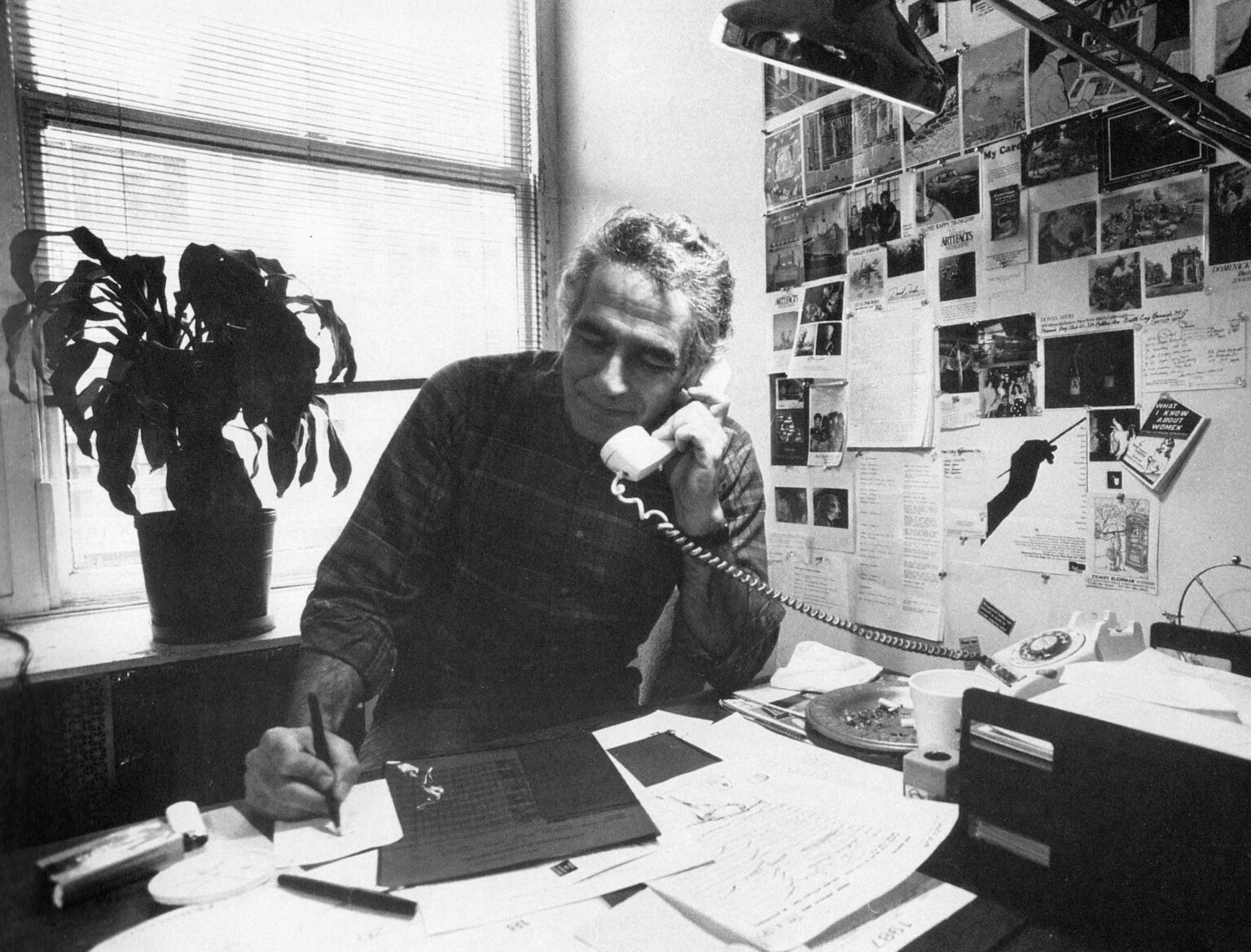

Sam’s illustration clients and assignments were incredibly diverse. He created art for book covers, TV ads, pharmaceutical brochures, magazine stories, and he even worked on film sets, including Paul Mazursky’s “Next Stop Greenwich Village.” As demand for illustration ebbed by the late seventies, demand for Sam’s teaching expertise exploded and his students were among the few to launch successful careers during that period. He taught Illustration Portfolio, Pictorial Problems in Illustration, and at least five figure drawing classes each week at SVA. He also taught at Pratt Institute and Marywood University’s MFA summer program in Scranton.

At SVA, Sam taught figure drawing to undergrad and continuing ed students in Room 501, which he shared with Jack Potter. He gave each student personal attention and helped them understand how to translate the poses into interesting drawings. He exposed his classes to the works of great artists and illustrators and discussed what made each of them distinct. He encouraged students to take chances, understand what they were seeing, think about how they could define form and shape, consider lines and edits, and ultimately develop an individual voice.

Students in his illustration classes would routinely dominate student competitions at the Society of Illustrators. Each winning piece was completely different but displayed a competency that only comes with a thorough understanding of process, vision, and identity.

Sam’s working-class New York accent and few malapropisms belied the fact that he was an extremely cultured, well-read sophisticate. He constantly toured museums and galleries in New York and abroad, amassed a collection of rare art books, and was obsessed with the act of creating art — forever drawing or painting other commuters, his family members, models in Long Island studios, and sometimes he would just doodle while watching TV. He also played the trumpet, played tennis, loved foreign-language films, spoke French, and he traveled the world extensively with his family. He would draw throughout each vacation, of course.

Sam was never nostalgic about his commercial illustration career. He didn’t save any originals or printed samples — not even of his award-winning work. His most impactful talent was that as a teacher. When asked if any of his own instructors informed his style, he said, “Not at all. The way I teach is almost in reaction to how I was taught. Many of my famous teachers didn’t know how to communicate well. I had one who would set-up the model and then sit in the corner to read the newspaper and drink coffee.”

Sam retired from teaching in 2005. Until recently, his personal artwork featured on this site was seen only by those who were in the room when he created it.

— Alex Knowlton, February 12, 2021

If you are a colleague, friend, or former student of his, please share your memories. His surviving family members, particularly his two daughters and six grandchildren, would appreciate learning more about his role in your life.